POLICY BRIEF | The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: how to make it work for developing countries

This article presents a summary of the Policy Brief ‘The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: how to make it work for developing countries’ by Sam Lowe, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for European Reform

The EU intends to introduce a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) by the end of 2021. While the exact design is not yet known, the CBAM would see a charge levied at the border, proportionate to the carbon emitted during the production of imported goods. The EU’s proposed CBAM risks unfairly penalising the exports of developing countries. While all countries should accept responsibility for tackling a shared global threat such as climate change, it is unreasonable to expect poorer countries to shoulder the same burden as those that are richer and have historically contributed a larger share of cumulative carbon emissions.

Why is the EU pursuing a CBAM?

The CBAM will form part of a broader package of EU measures called the European Green Deal, designed to help the EU become carbon neutral by 2050. More specifically, the CBAM is being introduced to reduce the risk of ‘carbon leakage’ – when companies move production from jurisdictions with strict emission regimes to those with weaker ones – to produce goods more cheaply. If the EU’s climate measures do not manage the risks of carbon leakage, they could lead to the EU’s emissions largely moving elsewhere rather than being reduced.

How would an EU CBAM work in practice?

At the time of writing, the exact design of the EU’s proposed CBAM remains unknown. But irrespective of the exact approach, the CBAM will need to conform to some set principles if it is to be compatible with the EU’s World Trade Organisation (WTO) commitments.

To be consistent with the EU’s WTO commitments, and legally defensible, the EU’s CBAM can only apply to sectors which are also subject to an internal EU carbon price. In practice, this constraint would limit the CBAM’s scope to sectors currently covered by the ETS – energy-intensive industries including oil refineries, steel and metal works, cement, paper, and some basic chemicals.

For third countries exporting to the EU, beyond sectoral coverage of the CBAM, the exemptions matter, too: under what circumstances would imported goods not be subject to an EU CBAM levy, despite falling under the sectoral coverage of the scheme? Here there will probably be two routes available:

- Countries that have a similar domestic carbon price to the EU could be granted equivalence, meaning that exports originating in their territory would not be subject to the EU’s CBAM, so as to avoid double carbon taxation. Partial equivalence is also a possibility – countries which have an internal carbon price, but set lower than the EU’s, could see their exports to the EU benefiting from a reduced CBAM levy.

- Imported goods that have been produced with fewer emissions than their EU equivalents could be subject to a proportionally reduced charge. For example, if an importer of ceramics could demonstrate that they had been produced using zero-carbon geothermal kilns, the imported ceramics would not face a CBAM charge even if they originated from a country without an equivalent domestic carbon price to the EU and ceramics were covered by the CBAM.

What is the risk to developing countries?

In theory, an EU CBAM could negatively impact the development of poorer countries, and reduce opportunities for export-led development. The Bank of Finland estimates that a CBAM of $28 per tonne of CO2 on imports is equivalent to an average import tariff of 2 per cent. Depending on the developing country’s export mix, the applied EU ‘tariff’ could be higher or lower – imports from India, for example, would face a 4 per cent tariff according to the study. As the carbon price increases, so would the effective tariff. The IMF estimates that a carbon price of around $75 per tonne of CO2 will need to be in place by 2030 if the rise in global temperatures is to remain below 2 degrees. That will require the effective carbon price in the EU to almost triple, implying an effective average applied CBAM tariff of around 6 per cent, barring a change in technology or policy in the exporting country.

Developing country exporters could face a significant barrier to trading with the EU. Most developing countries currently have tariff and quota free access to the EU market, as a result of EU unilateral preference schemes or economic partnership agreements. But an EU CBAM could dent this relative advantage if it applied to developing countries’ exports, but exempted many developed country exports, either because they originated from countries that had introduced their own equivalent domestic carbon price or because companies’ production processes were more carbon-efficient.

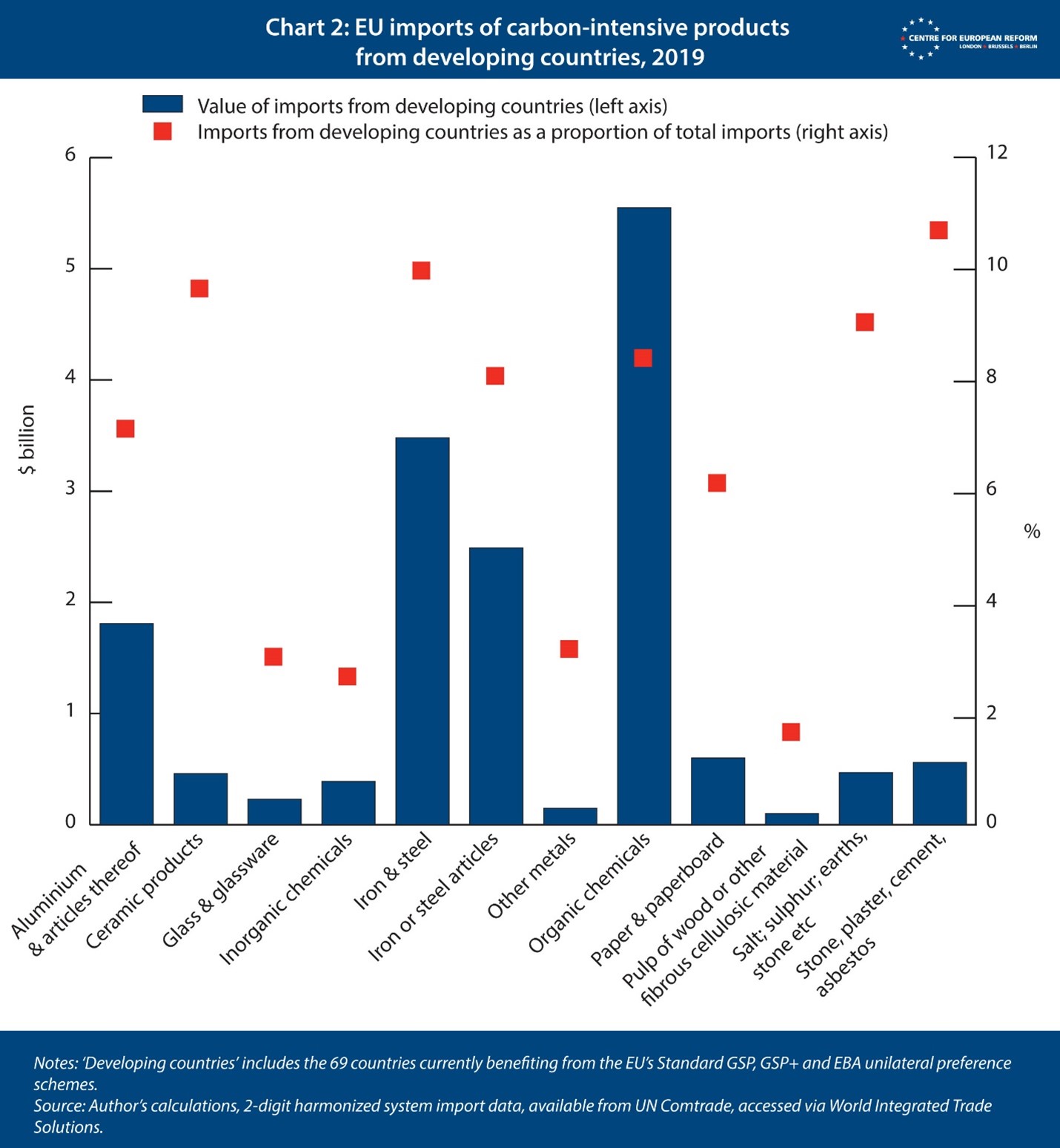

Assuming an EU CBAM initially only covers goods covered by its ETS, developing countries could see exports to the EU worth $16 billion subject to the new CBAM levy. Chart 2 shows the value of EU imports from developing countries for a range of goods that are currently covered by the ETS, as well as the share of total imports for each product type from developing countries. Exempting developing countries from the CBAM would not be particularly costly for the EU in the context of its total imports – of all the sectors covered, only imports of stone, plaster and cement from developing countries account for over 10 per cent of total imports (although other sectors such as iron and steel come close). However, for developing countries, additional CBAM-related costs could prove to be very damaging.

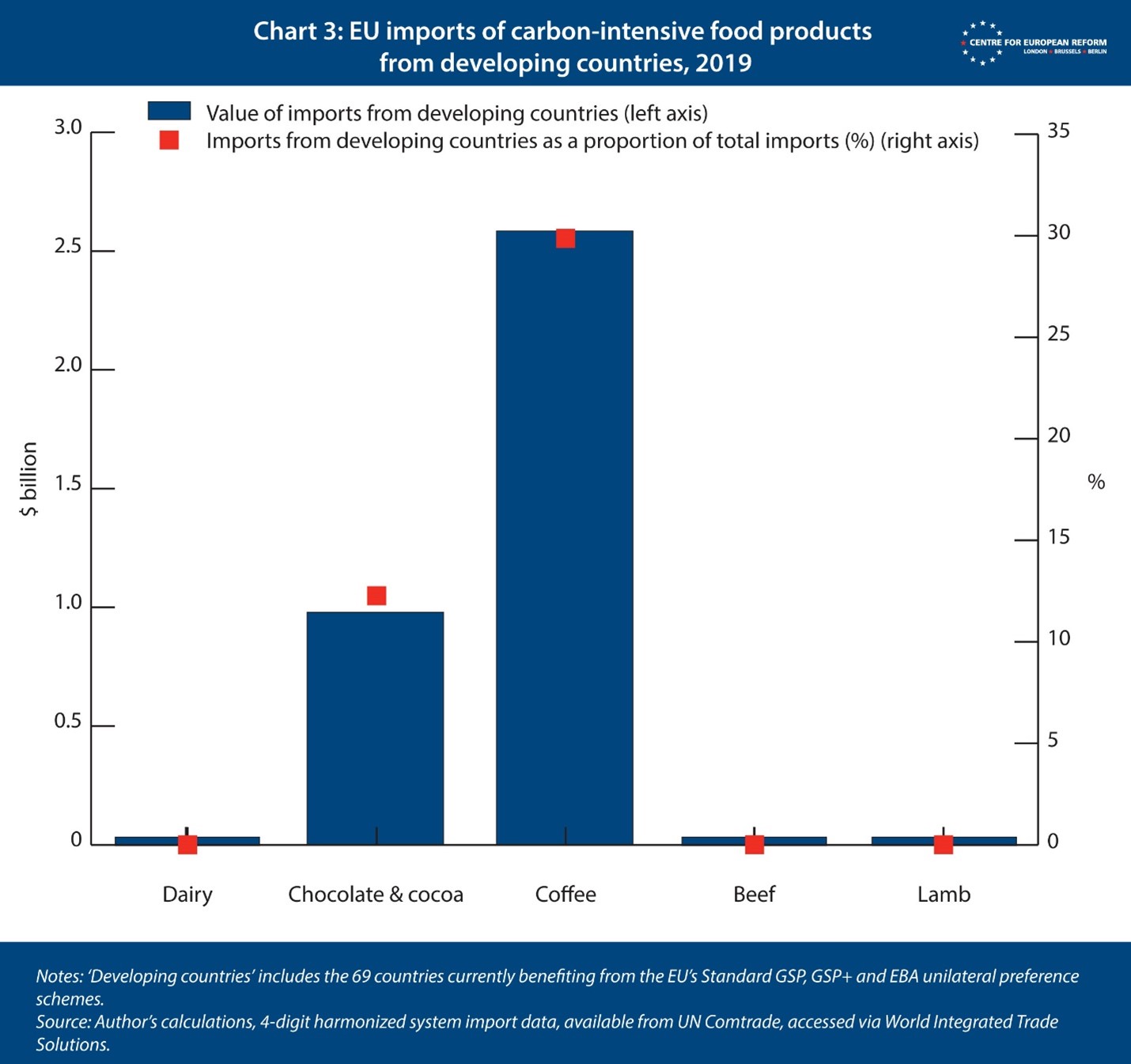

If the EU were to expand the CBAM to cover more sectors, as advocated by the European Parliament’s environment committee, developing countries could find themselves even more exposed to the CBAM. Were agricultural emissions to be targeted, for example, an additional $3.6 billion of developing country trade could be subject to the CBAM (Chart 3). But developing countries do not currently export much in the way of carbon-intensive food products such as beef and dairy to the EU, because they are unable to meet EU food safety standards – Vietnam was the only GSP beneficiary to export any beef to the EU in 2019.

Furthermore, CO2 imported from developing countries accounts for only a small proportion the CO2 embodied in final EU demand – for example, imported CO2 from India, the third largest carbon emitter in the world, only accounts for just over one per cent of the CO2 embodied in final EU demand. Of the countries covered by the EU’s unilateral preference schemes, the next largest sources of CO2 consumed in the EU, Indonesia and Vietnam, contribute around six times less than India.

How to accommodate developing countries

It is in the EU’s interest to ensure that a CBAM does not unfairly penalise developing country exporters. Subjecting these exporters to a CBAM could lead to the EU undermining the multilateral approach to climate mitigation, by compromising the notion of differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accommodating developing countries could also ensure that the CBAM does not come into conflict with the EU’s development objectives.

From a legal perspective, there is a precedent for discriminating in favour of developing countries.

From a legal perspective, there is a precedent for discriminating in favour of developing countries. The EU already uses the flexibility afforded by the WTO General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade’s (GATT) so-called enabling clause to unilaterally grant developing countries preferential access to its market under its GSP schemes.

The EU could similarly justify the full or partial exemption of countries currently covered by its unilateral preference schemes from its CBAM. Here, as it does with its trade preferences, the EU should differentiate between LDCs and lower-middle-income countries – offering a full, unconditional exemption to the former, and conditional exemptions to the latter.

How to exclude LDCs from an EU CBAM

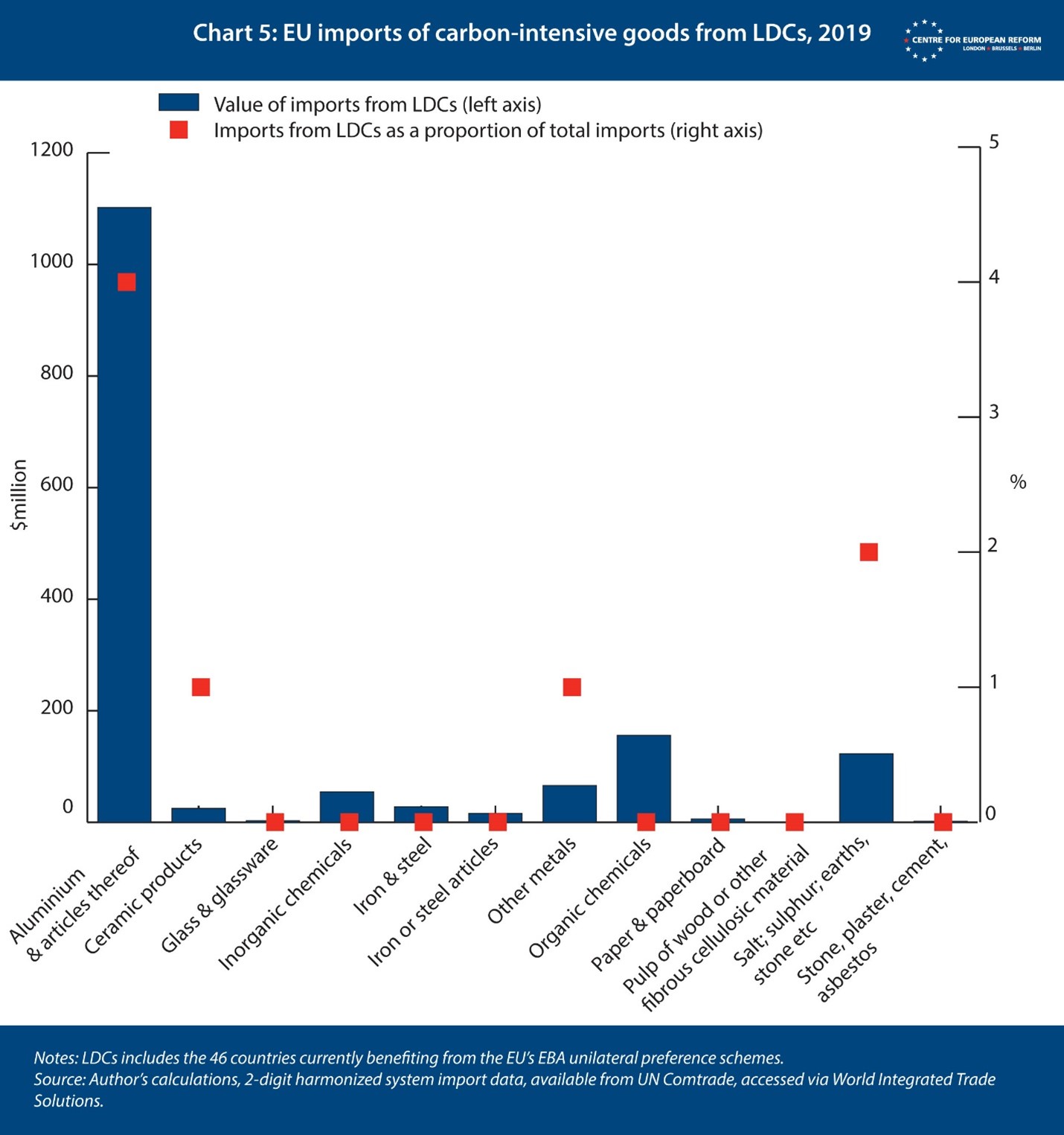

Goods originating from the 46 LDCs should be fully excluded from the EU CBAM to avoid penalising their exporters. From an EU perspective, the low volumes of LDC imports means there is little risk that a blanket exemption will encourage carbon leakage. Looking solely at EU imports of carbon-intensive goods from LDCs, Chart 5 shows that, as a proportion of total imports, only LDC imports of aluminium come close to being of any overall significance, at just under 5 per cent of the EU’s total aluminium imports.

How to exclude lower-middle-income countries from an EU CBAM

Lower-middle-income countries pose a different set of problems for the EU, as some of them are large net contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions, and host internationally competitive industries. A blanket CBAM exemption could discourage transition to lower-carbon production methods, but equally full application of the CBAM could unfairly penalise nascent industries in countries that are still in need of further development.

Here, the EU should exempt imports from countries benefiting from its standard GSP or GSP+ unilateral preference schemes, until imports of a product reach a threshold that indicates the sector is already developed and internationally competitive. For example, the GSP schemes currently only allow tariff-free access to the EU until the average value of imports of a specific product from a GSP beneficiary country exceeds a given threshold. The threshold is calculated as a percentage of the total value of EU imports of the same product from all GSP beneficiary countries – and is usually set at 57 per cent.

The EU could adopt a similar approach when deciding whether imports from standard GSP and GSP+ countries are exempt from its CBAM or not. This would mean that imports from GSP and GSP+ countries were exempt from the CBAM until the average value of EU imports of a given product exceeds 57 per cent of the total value of EU imports of the same product from all GSP beneficiary countries. Such an approach, for example, would see the CBAM levy apply to imports of Indian iron and steel, which accounts for well over 57 per cent of all iron and steel imported from GSP beneficiaries, but not to iron and steel imports from Indonesia, Vietnam and others. Alternatively, the EU could introduce a bespoke CBAM threshold with its own criteria.

Rules of origin

The ability to determine where an imported product originates from is central to any CBAM. Without origin requirements, goods could be produced in a country without an equivalent domestic carbon price to the EU and then shipped to the EU via a country with such a carbon price, to take advantage of the CBAM exemption. However, this issue can be addressed using existing measures, as rules determining the origin of specific imported goods matter in international trade regardless of carbon pricing. There are two existing EU approaches to assessing origin – preferential rules of origin which determine whether imports qualify for a trade agreement or unilateral preference scheme, and non-preferential rules of origin which are relied on when trading on the basis of the EU’s WTO commitments:

- The EU could rely on its existing GSP preferential rules of origin. If an import met the rules of origin requirement of the EBA, Standard GSP or GSP+ schemes, and therefore qualified for preferential tariffs when entering the EU, it would also be exempt from the CBAM. However, these rules of origin can be overly burdensome, leading to some exporters not taking advantage of the schemes. The last major (and slightly dated) EU review found that in 2016 the average uptake (on a country-by-country basis) of the preferential trading arrangements, or preference utilisation rate, for exports to the EU from countries covered by GSP schemes, was 56 per cent.

- The EU could instead rely on its non-preferential rules of origin which come with a significantly reduced compliance burden. The advantage here is that all EU importers already have to comply with these – so it would not be an additional burden for developing country exporters. Moreover, the EU already uses non-preferential rules of origin to police anti-dumping measures.

In practice, the amount of developing country CO2 embedded in final EU demand is small enough to be considered immaterial.

Either way, the EU will need to be able to determine where imported goods come from.

Safeguards

In the unlikely event that imports from a developing country could be directly linked to carbon leakage, the EU can retain the right to trigger safeguard measures, and, for example, apply the CBAM levy to specific imports. Safeguard measures are not uncommon, and exist within the WTO framework, as well as in most trade agreements and the GSP regime. The EU recently imposed tariffs on rice from Cambodia and Myanmar, despite both countries being beneficiaries of the EBA scheme, because their low prices hurt EU producers (while benefitting EU consumers, of course).

Concerns and considerations

There are arguments against providing exemptions for developing countries. Exemptions could undermine the EU’s legal rationale for a CBAM, leave the door open for carbon leakage and remove an incentive for policy-makers in the developing world to transition their economies away from high carbon energy sources, and carbon-intensive production methods. However, none of these arguments stand up to scrutiny.

CBAM legal basis

For the CBAM to be compatible with the EU’s WTO commitments, the EU will need to ensure that it does not discriminate against imported goods, and that the import levy is equivalent to the cost imposed on domestic industry by an internal tax or similar measure (as per GATT Article II.2 (a)). It should also be explicitly designed for the purpose of effectively reducing EU carbon emissions. This is to ensure that even if the CBAM is found to be discriminatory, it could still be justifiable under GATT’s environmental exception (Article XX (b) and (g)).

Exempting developing countries could undermine the environmental justification for the CBAM, if it led to a large amount of offshore emissions being ignored. However, in practice, the amount of developing country CO2 embedded in final EU demand is small enough to be considered immaterial. As Chart 4 demonstrates, the only country contributing more than one percentage point to CO2 embodied in final EU demand is India, and India’s most carbon intensive exports would probably be covered by the CBAM mechanism anyway, if applied according to the recommendations made in this paper.

Opportunities for carbon leakage

Exemptions could theoretically create new opportunities for carbon leakage, and reduce the political incentives for developing world governments to decarbonise their economies. However, again, this would not pose a problem in practice.

The exemptions proposed in this paper are only temporary, in that they would only apply unconditionally to the least developed countries, and conditionally to lower-middle income countries. As countries become richer, and their industries more internationally competitive, they will graduate out of these exemptions. As such, there is still an incentive for these countries to pursue low-carbon growth as well as the introduction of domestic carbon pricing instruments – in their absence their exports to the EU would be subject to its CBAM once the exemptions ceased to apply. The EU would also be able to trigger the CBAM’s safeguard mechanisms in the event that it experienced a surge in carbon intensive imports from an exempt country.

Conclusion

The EU has ambitious development and climate agendas. It is important that both are reflected when designing the CBAM. Ensuring that its CBAM does not undermine its broader development objectives, and takes into account the existing international principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’, should be a priority for the EU. From a more self-interested perspective, for the EU to include measures that address the concerns of developing countries would also reduce the risk of the CBAM facing legal challenges from aggrieved WTO members.

This paper suggests one potential solution, but exempting developing countries from the EU’s CBAM should not be considered in isolation. As well as CBAM exemptions, the EU must consider how else it can support decarbonisation efforts in the developing world. This should involve a discussion about how the money raised by a CBAM should be spent, and whether it could be allocated to specific development projects. Regardless, the potential impact of a CBAM on developing countries cannot be ignored. Solutions building on existing EU schemes are readily available and pose little risk to the EU’s wider carbon-reduction objectives.

This article provides a summary of the key findings of the policy brief titled " The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: How To Make It Work For Developing Countries" and was first published by the Centre for European Policy Reform in cooperation with the Open Society European Policy Institute: https://www.cer.eu/publications/archive/policy-brief/2021/eus-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-how-make-it-work. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the GSP Hub.

Share your views below and engage in the discussion!